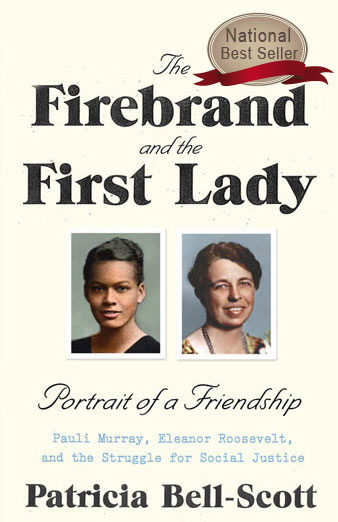

// The Firebrand and the First Lady //

Patricia Bell-Scott’s groundbreaking biography, The Firebrand and the First Lady—two decades in the works—tells the story of how a brilliant writer-turned-activist, who was the granddaughter of a mulatto slave, and the first lady of the United States, whose ancestry gave her membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution, forged an enduring friendship that changed each of their lives, enriched the conversation about race, and added vital fuel to the movement for human rights in America.

Pauli Murray first saw Eleanor Roosevelt in 1933, at the height of the Depression, at a government-sponsored, two-hundred-acre camp for unemployed women where Murray was living, something the first lady had pushed her husband to set up in her effort to do what she could for working women and the poor. The first lady appeared one day unannounced, behind the wheel of her car, her secretary and a man Murray presumed to be a Secret Service agent as passengers. To Murray, then aged twenty-three, Roosevelt’s self-assurance was a symbol of women’s independence, a symbol that endured throughout Murray’s life.

Five years later, Murray wrote a letter to Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt protesting racial segregation in the South. Murray’s letter was prompted by a speech the president had given at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, praising the school for its commitment to social progress. Pauli Murray had applied for and would be denied admission to UNC graduate school because of her race.

She wrote in her letter of 1938:

“Does it mean that Negro students in the South will be allowed to sit down with white students and study a problem which is fundamental and mutual to both groups? Does it mean that the University of North Carolina is ready to open its doors to Negro students … ? Or does it mean, that everything you said has no meaning for us as Negroes, that again we are to be set aside and passed over … ?”

The president’s staff forwarded the letter to the federal Office of Education. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote back to Murray: “I have read the copy of the letter you sent me and I understand perfectly, but great changes come slowly … The South is changing, but don’t push too fast.”

So began a friendship between Pauli Murray (poet, intellectual rebel, principal strategist in the fight to preserve Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, cofounder of the National Organization for Women, and the first African American female Episcopal priest) and Eleanor Roosevelt (first lady of the United States, later first chair of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, and chair of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women) that would last for a quarter of a century.

It was a decades-long friendship — tender, moving, prodding, inspiring — sustained primarily through correspondence and characterized by brutal honesty, mutual admiration, and respect, revealing the generational and political differences each had to overcome in order to support each other’s growth as the transformative leaders for which they would be later known.

Of the two extraordinary women, one was at the center of world power; the other, an outsider ostracized by multiple discriminations, fighting with heart, soul, and intellect to push the world forward (she did!) and to become the figure for change she knew she was meant to be; each alike in many ways: losing both parents as children, being reared by elderly kin; each a devoted Episcopalian with an abiding compassion for the helpless; each possessed of boundless energy and fortitude yet susceptible to low spirits and anxiety; each in a battle against shyness, learning to be outspoken; each at her best when engaged in meaningful, important work. And each in her own society sidelined as a woman, and determined to up-end the centuries-old social constriction.

Drawing on letters, journals, published and unpublished documents, and interviews, Patricia Bell-Scott, professor emerita of women’s studies and human development and family science at the University of Georgia, presents the first close-up portrait of this evolving friendship and how it was sustained over time, what each gave to the other, and how their friendship changed the cause of American social justice.